Why the Greek Septuagint?

The early Church prefered to use the Greek Septuagint version of the Old Testament (also known as the LXX) over more recent translations from Hebrew.

That’s why we use the Greek Septuagint for our Old Testament. In addition:

- It’s the oldest surviving Bible text, ~600 years older than our oldest Hebrew copy.

- When the Apostles quote the Old Testament, their quotes match the Greek Septuagint 92.7% of the time, versus only 76% of the time with the traditional Hebrew text.

- The Greek text contains prophecies about Jesus that the Hebrew text words differently, sometimes in ways that invalidate the prophecy.

- The Greek text has a more accurate chronology that matches better with the historical record.

- The Greek text clarifies many ambiguities in the Hebrew text.

This article explores the topic in more detail.

Contents

What is the Greek Septuagint?

The Greek Septuagint is an ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures, created between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, made in a particular dialect called Koine Greek.

Legend has it that 72 Jewish scholars produced it, working on the island of Pharos in Alexandria, Egypt — the island where the famous Pharos Lighthouse stood. The 72 scholars give it its name, Septuagint, which means ‘seventy’ in Latin. That’s also why it’s also called the LXX (seventy in Roman numerals).

We’ve found fragments of these Greek manuscripts dating back to the 2nd century BC — making them among the very oldest surviving Bible texts!

Why did they make it? By this time, many Jews lived outside Israel and spoke Greek, which was the international language of the day (like English in our modern world). They needed their sacred texts in a language they could understand.

But here’s the shocking part: when we compare this ancient Greek translation to our current Hebrew texts, we find some surprising differences. Sometimes these just reflect the natural changes you see when translating from one language to another, but other times, they suggest that the Hebrew text was later changed in some places.

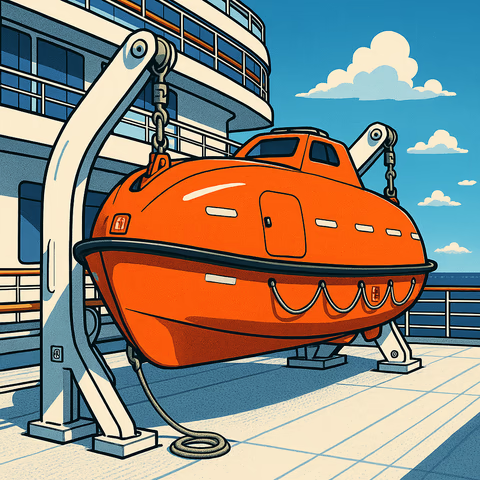

This suggests that the Greek Septuagint is like a lifeboat, preserving some original Bible texts.

Some differences are significant enough to change our understanding of biblical chronology, prophecies, and even Jesus himself!

The Historical Witnesses for the Septuagint

How do we know the Septuagint preserves an older, more accurate version of the Bible? Because we’ve got witnesses – lots of them!

Jesus and the Apostles’ Quotations

Here’s the most compelling evidence:

-

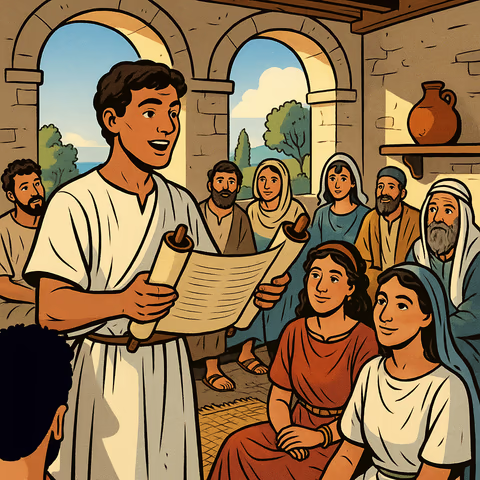

When Jesus and his apostles quoted from the Old Testament, their quotes match the wording in the Greek Septuagint 92.7% of the time (242 out of 261).

-

They match the Hebrew Text we have today only 76.24% of the time (199 out of 261).

The New Testament writers likely knew the Hebrew text well; they were reading or listening to Hebrew or Aramaic scrolls every week in their synagogues. Yet their quotes still match the Septuagint, suggesting that their Hebrew or Aramaic Bibles matched up too.

Remember, Jesus grew up in Nazareth, where few people spoke Greek. He wasn’t reading from a Greek translation, but from Hebrew texts that likely matched what we now find in the Septuagint.

Early Christian Quotes

The very earliest Christian writers consistently quoted from versions of the Old Testament that matched the Septuagint.

Josephus

The famous Jewish historian Josephus, writing in the 1st century AD, quotes Bible passages that match the Septuagint but differ from our modern Hebrew text.

Why is this significant? Because Josephus was writing before the Hebrew text was changed! As a respected Jewish historian with access to the Temple records, his testimony is invaluable.

Other Early Jewish Historians

It seems that the Septuagint’s chronology was widely-accepted by Jews at one time.

-

The Jewish historian Eupolemus from the 2nd century BC reported a chronolgy matching the Septuagint’s in his historical writings.

-

Even earlier, another Jewish historian, Demetrius the Chronographer from the 3rd century BC, gave his chronology with the same dates.

-

Then, in the 1st or 2nd century AD, Pseudo-Philo (an unknown author) who wrote Biblical Antiquities also followed a similar timeline.

The Dead Sea Scrolls

With the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran, (which date back to the 1st century BC), scholars found that some Hebrew manuscripts often matched the Septuagint rather than our current Hebrew text. Think about it: these ancient Hebrew scrolls sometimes agree with the Greek translation more than they do with the later Hebrew version!

The Samaritan Pentateuch

The Samaritan Pentateuch (2nd century BC) agrees with part of the Septuagint’s chronology (after Noah’s day). This work is a copy of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, but with some changes to suit their sect’s belief.

However, the fact that their copy of those Bible books happens to mostly match the Septuagint is not surprising if the Hebrew text underwent later changes.

Ancient Rabbinical Writings

Even the early Jewish rabbis, in their writings before the 2nd century AD, quote Bible passages that align with the Septuagint, not the Hebrew text we have today.

Yes, Jewish scholars were simply referring to their scriptures as they knew them, and they used words like the Septuagint.

Justin Martyr’s Testimony

In the mid-2nd century AD, the early Christian writer Justin Martyr openly accused Jewish leaders of changing their Bible text. In his famous Dialogue with Trypho, he even had to use their new version when arguing with Jews about the Messiah, because they wouldn’t accept quotes from the older version that Christians used.

Justin was documenting a historical change that we can still trace in manuscripts today. It appears to be a mixture of two things:

- Hebrew scholars and scribes choosing existing variants that sound less supportive of Jesus.

- A few new deliberate changes to the Hebrew text, such as the changes to the chronology of Genesis.

The Chronology of Genesis May Have Been Changed

The chronology of Genesis is a good example of suspected changes to the Hebrew text. As we mentioned (above), the old chronology was widely accepted by both Jews and Christians up to the 2nd century AD, including by historians; but then, it suddenly changed.

Centuries of time suddenly vanished from Genesis! What happened? There wasn’t any removal of historical events or anything like that, no, instead the lifespans of the patriarchs were collectively shortened.

How did that happen?

While it’s possible that it was some bizarre accident, is it likely that such a widely-known chronology could be changed so radically without anyone noticing? Some historians believe the chronology in the Hebrew text of Genesis was changed deliberately to counter Christian claims about Jesus being a High Priest ‘in the order of Melchizedek.’

You see, Christians called Jesus their High Priest, but only people from the tribe of Levi could be priests, and Jesus was from Judah! So Christians, like Paul, pointed to Melchizedek, a priest who served God centuries before the tribe of Levi existed (Hebrews 7:15). Indeed, Psalm 110:4 prophesies that the Messiah would be a priest:

‘in the order of Melchizedek.’

The theory goes that the Pharisees came up with a solution: They claimed Melchizedek was just another name for Noah’s son Shem, and was, therefore, an ancestor of Levi — completely destroying the Christian argument!

Yet there was a problem: according to the Genesis timeline, Shem had been dead for centuries by the time Melchizedek was mentioned! They could not be the same person at all.

So, some believe that they simply removed enough years from the Genesis chronology to make it look like Shem and Melchizedek were around at the same time.

Certainly, by the Middle Ages, this was the established Rabbinical tradition, and it’s what’s taught today, that Shem was Melchizedek. Yet, it is mathematically impossible using the original timeline accepted by everyone before the 2nd century AD. So, the theory goes, 2nd century Rabbinical school ‘corrected’ the text.

It’s hard to say if that’s what really happened, and it’s a compelling theory, but we really don’t know.

- View our Chronology based on the Septuagint

Not Acceptable in Later Years!

Obivously, later Rabbis and modern Jews would never dream of altering the sacred text — their respect for scripture is enormous. Indeed, the later Masorete scribes went to incredible and borderline-obsessive lengths to preserve every letter exactly as they received it.

The changes we’re discussing, if they really happened in that way, would have occured during a specific crisis period in the late 1st/early 2nd century AD, when a small group apparently felt desperate measures were needed to prevent more Jews from converting to Christianity. If guilty of this, then they acted on their own, and would bare the guilt all by themselves (Deuteronomy 24:16). Later Jewish scholars preserved the Hebrew text to a superb degree.

The Septuagint’s Agreement with Dating and Archaeology

Archaeological discoveries keep confirming the Septuagint’s timeline.

The fall of Jericho is just one example. Archaeological evidence and carbon dating place its destruction in the mid-1500s BC. The Hebrew text’s chronology can’t accommodate this date, but the Septuagint’s timeline (placing the event 40 years after the departure from Egypt in 1525 BC) aligns beautifully with the evidence.

Similar patterns emerge at numerous other Biblical sites, where carbon dating consistently favors the Septuagint’s chronology over the Hebrew text’s compressed timeline.

Egyptian Historical Timeline

The Septuagint’s dates work remarkably well with Egyptian history. For example, it places the Great Downpour (the flood of Noah) around 3350 BC, followed by the first Egyptian Dynasty in 3050 BC, which is a perfectly reasonable gap for a new civilization to begin. The Hebrew text, however, would have Egypt’s dynasties beginning before the Flood!

Even more intriguing? The Septuagint’s dating of Adam’s creation (about 5500-5600 BC) aligns closely with the start of history according to the Egyptians (5550 BC). Coincidence?

Chinese Civilization Dates

Here’s another correlation: archaeologists trace Chinese civilization back about 5,000 years.

That’s impossible with the Hebrew text’s timeline (which puts Noah leaving the chest just ~4,350 years ago), but fits perfectly with the Septuagint’s chronology of the Flood occurring around 5,400 years ago.

Mayan Calendar Correlation

Did you know the Mayan calendar records a great flood ending their fourth age in 3113 BC? That’s just 100-200 years different from our Septuagint-based calculation of the Biblical Flood!

If we exclude one disputed genealogical entry, the difference shrinks to only around 70 years.

Population Growth Mathematics

Let’s talk simple math. The Hebrew text’s compressed timeline creates some impossible situations. Here’s a striking example:

According to the Hebrew text, there were only 67 years between the Flood and the birth of Shem’s great-great-grandson Heber. Yet during this same period, Noah’s great-grandson Nimrod was already building Babylon and several other cities across an area the size of modern Iraq (Genesis 10:6-12).

So here’s the big question: Where did all the people come from to build and inhabit those cities in less than 67 years?

Let’s run the numbers:

Even with extremely generous assumptions (every woman aged 20+ having a baby every single year), a population starting with 8 people would only grow to about 5,532 persons in 67 years. And here’s the kicker: only 892 of those would be adults! The other 4,640 humans would all be babies, toddlers, children, and teenagers.

Could Nimrod have built a ‘kingdom’ with multiple cities using just 892 adults? Actually, it’s even more unrealistic than that, because this calculation assumes:

- Nobody ever died

- No stillbirths occurred

- No miscarriages happened

- No deaths during childbirth

- Perfect conditions for survival

Let’s try a more realistic calculation. The highest natural population growth rate seen in any country today is 3.5% per year (for comparison, the highest global growth rate in recorded history was just 2%). Using this generous 3.5% rate, a population of 8 people would grow to only about… 80 people in 67 years.

Now look at the Septuagint’s timeline instead. It shows about 400 years between leaving the Ark and the birth of Heber (around the time of Nimrod). With that same 3.5% growth rate, the Earth’s population could have reached 6.8 million by the time Nimrod built his cities.

Which timeline makes more sense? The Hebrew text’s timeline which requires impossible population growth, or the Septuagint’s chronology which allows for realistic human expansion?

We say that the Septuagint’s accuracy is simple mathematical reality.

Carbon Dating: Reliable up to 5,000 years

Carbon dating is highly accurate for more recent periods, only becoming less reliable beyond about 5,000 years. This is because it relies on carbon-14 to be created at pretty much constant rate. If atmospheric changes mean it’s created at a higher or lower rate, the ‘clock’ is thrown off.

For this reason, the method is thought to be extremely reliable up to about 2,000 years ago, then less so, becoming very unreliable beyond 5,000 years.

Interestingly, 5,000 years ago is around the time of the Biblical Flood according to the Septuagint’s chronology (only 4,300 years ago in the Hebrew Masoretic Text). Assuming the planet and atmosphere took some centuries to settle down, 5,000 years ago is exactly where we’d expect major atmospheric changes to affect carbon-14 formation.

The key point? When we use the Septuagint’s chronology, archaeological evidence stops being a problem and starts becoming a corroborative witness to the Bible’s accounts in new ways that it was not before.

The Septuagint’s Textual Excellence

The Prophecies of Jesus that the Christians Knew

Most importantly, the Septuagint preserves Messianic prophecies in the forms that the early Christians would have read them. Many prophecies that clearly point to Jesus in the Septuagint appear vague or altered in the Hebrew text. This is either because the original text was changed, or because variants existed which are now lost, or that the Greek translator understood what the idioms actually meant, and translated them plainly for us.

For example, consider the 40th Psalm, verse 6, which says in the Hebrew text:

‘my ears you have opened’

But the Septuagint’s version of Psalm 40:6 says:

‘a body you have prepared for me’

Which version did the writer of Hebrews quote when speaking about Jesus? The Septuagint version, at Hebrews 10:5! This is a profound prophecy about Jesus taking human form, of great importance to the argument in Hebrews.

It could represent:

- An earlier version of the text which was lost.

- An earlier version of the text which was later changed.

- An older variant of the text which was lost.

- Or an interpretation that was only understood when the Greek Septuagint was translated.

Whatever really happened, the Septuagint preserves these prophecies, and their meanings, in a way that the Hebrew text does not. We can see why early Christians found such clear evidence for Jesus in the Old Testament; their text pointed to him more than our text today!

Want to see more examples? Check out our complete guide to the Restored Messianic Prophecies.

It Makes More Sense!

Consider the book of Isaiah. Some scholars claim the Septuagint version is ‘totally different’ from the Hebrew – and they’re right! But here’s the surprising part: the Septuagint’s version makes more sense. It’s clearer, reads more naturally, and maintains better narrative flow throughout.

The same is true for Proverbs. The Septuagint’s version differs significantly from the Hebrew text, but it has a better natural rhythm and a more coherent structure. Could the Septuagint preserve a more accurate version of Solomon’s original writing, taken from a time before the Hebrew text was changed?

Name Accuracy and Pronunciation

The Septuagint provides unique insights into how Hebrew names were actually pronounced over 2,200 years ago. Remember, ancient Hebrew had no vowel point, so no one really knows how most words were originally pronounced. The Septuagint gives us a snapshot of how Hebrew-speaking Jews thought these names should sound in Greek.

Sometimes the names are entirely different, or reveal the original meanings behind them. For example, the Septuagint doesn’t mention a ‘Garden of Eden’ at all; instead, it describes a ‘Paradise of Delights’ located in ‘the Land of Edem’!

So Eden was never the name of the garden, it was the name of the region in which it was located.

Such distinctions help us better understand the original meaning of these ancient texts.

Resolution of Contradictions

The Septuagint often resolves apparent contradictions found in modern translations. Take Matthew 23:35, where Jesus mentions ‘Zechariah, son of Barachiah.’ Indeed, the prophet Zechariah’s father was called Barachiah (Zechariah 1:1). So what’s the problem? Well, the Hebrew text of 2 Chronicles seems to contradict this by calling him ‘son of Jehoiada’ instead! (2 Chronicles 24:20, MT)

The Septuagint resolves the mystery.

When you read that same verse in the Septuagint, you can see that the verse in 2 Chronicles wasn’t talking about the prophet Zechariah at all, but about someone else, a priest called Azariah! The Hebrew text was either accidentally corrupted there, or deliberately changed for some unknown reason.

Without the Septuagint, we would have no way to solve the contradiction.

Why Doesn’t Everyone Use the Septuagint?

You might be wondering: if the Septuagint is so good, why do most modern English Bibles use the Hebrew Masoretic text? The answer lies in a series of historical decisions, as well as bias and misunderstandings that still exist today.

Most western Bible translations can trace their Old Testament text choice back to the Protestant Reformation. The reformers, in their push to return to ‘original sources,’ chose to use the Hebrew Masoretic text — not understanding the issues we’ve discussed here.

However, the story really begins much earlier, in the 4th century AD.

Jerome’s Influence

When Jerome created his Latin Bible translation (the Vulgate) between AD 382-405, he made a fateful decision: he chose to translate from the Hebrew text available in his day rather than the Septuagint that Christians had used for centuries.

This wasn’t a universally popular decision! Major Christian figures protested, including Augustine of Hippo and even the Roman Emperor Theodosius II, who wrote to the Pope to object. But their protests were in vain.

Why did Jerome make this choice?

He believed that since Hebrew was the original language, it must be more reliable. He didn’t realize that the Hebrew text he was using had already been altered from its original form. His decision would have far-reaching consequences, as the resulting Latin Vulgate became the official Latin translation of the Church and formed the basis for most modern Bible translations today.

This single decision effectively disconnected western Christianity from the Bible text that Jesus and the Apostles had used. Isn’t it ironic that in trying to get closer to the ‘original,’ Jerome actually moved further away from it?

Eastern Orthodox Preservation

Interestingly, the Eastern Orthodox Church never abandoned the Septuagint. They’ve consistently used it as their primary Old Testament text for nearly 2,000 years. When western scholars claim the Septuagint is ‘just a translation,’ Orthodox Christians often reply, ‘It’s the translation the Apostles used!’

Modern Resistance Factors

Why don’t more scholars and translators return to the Septuagint today? Several factors create resistance:

- Tradition: Many theological traditions are based on Masoretic text readings.

- Investment: Existing Bible translations represent huge financial investments.

- Misconceptions: Many still believe ‘original Hebrew’ must be better.

- Academic Inertia: Changing established scholarly consensus is difficult.

Why Scholars Should Reconsider

The evidence for the Septuagint’s reliability keeps growing. Consider:

- Dead Sea Scrolls often agree with Septuagint readings.

- Many archaeological findings confirm Septuagint chronology.

- Ancient historical records align with Septuagint dates.

- Mathematical analysis supports Septuagint timelines.

- Early Christian writings consistently quote Septuagint versions.

Isn’t it time for western Bible scholarship to overcome its historical biases?

Common Objections Addressed

‘It’s just a translation! Why bother? Just go to the original Hebrew text!’

Yes, it is a translation, but it’s a translation made from Hebrew texts that existed over 2,300 years ago, representing our oldest Bible manuscripts. The Septuagint gives us a window into what the ancient Hebrew scrolls said centuries before anything else.

Remember: the oldest complete Hebrew manuscript (the Masoretic text) dates to the 9th century AD. Our Septuagint manuscripts are from the 3rd century AD (600 years earlier), which are copies of a translation made in the 3rd century BC, that’s about 1,200 years closer to the original texts!

To dismiss our oldest copy of the Old Testament out of hand, so callously, is incredibly unappreciative and betrays a total lack of understanding of textual criticism.

‘The original Hebrew must be better!’

This seems logical at first: surely the Hebrew text must be more accurate since it’s in the original language? But this argument ignores two crucial facts:

1. It doesn’t matter what the language is if the text has been altered.

Think about it: if someone was able to change the plays of William Shakespeare and set them all on a spaceship, could that person say:

‘This must be the more accurate text! Don’t you know that this is in English, the original language?’

Obviously, these people are missing the point entirely.

2. The Bible was written a long time ago, and much of the prophets wrote in poetry.

A lot of the Hebrew poetry is hard to understand, and therefore, hard to translate. Idioms and cultural references have been lost and forgotten over the centuries.

Therefore, the Septuagint’s translation is a very useful ‘second witness’ to tell us how those poems were understood by ancient Greek translators and their Greek-speaking Jewish community.

While some Septuagint books are translated very literally and are not so helpful, others translate the meaning, not just the words. Their reworded versions help explain to the Greek-speaking audience (who were less familiar with Hebrew ways) what the text is trying to say; they give it’s meaning, not just it’s vocabulary.

This is incredibly valuable for us today. Without it, the meaning of some verses would be entirely lost, or less certain.

To just dismiss all this, wave the hand, and say ‘the original Hebrew is much better’ is to miss the point entirely. How ignorant of history, and how unappreciative of an ancient text’s value.

‘The Septuagint has too much Greek influence!’

Some argue that the Jewish translators were influenced by Greek philosophy when creating the Septuagint. While this is certainly true in some word choices (translators must choose terms their readers will understand), it doesn’t explain why the Dead Sea Scrolls (written in Hebrew) often agree with the Septuagint against the later Masoretic text.

Besides, if Greek influence was really so bad that we should dismiss it today, why did the Apostles and other Greek-speaking Jews quote from the Septuagint freely? And why would Jewish writers from before the 2nd century quote Hebrew wording that matches the Septuagint?

We conclude that these ancient people did not feel there was enough Greek influence to complain about, and they lived a lot closer to these issue than we do today.

‘Only the Pentateuch part of the Septuagint was original!’

This is a fringe conspiracy theory. The claim is that only the first five books (the Pentateuch) were part of the original Septuagint, and the rest was a ‘Christian forgery’! This shows itself to be little more an excuse, as it falls apart when we look at the evidence:

- Many readings in the Dead Sea Scrolls (pre-Christian) match Septuagint readings.

- Josephus (1st century Jewish historian) quotes from all over of the Septuagint.

- Pre-Christian Jewish writers reference the wider Septuagint.

As you can see, this is merely an excuse, usually put about by people who have very little knowledge of the facts. It’s usually trotted out by people who don’t like what the Septuagint says somewhere, and want some easy ‘just like that’ way to dismiss it. Unfortunately, life isn’t that simple, and only people with very little historical knowledge would fall for this.

‘The Septuagint was changed to please Egyptian King Ptolemy!’

Another borderline conspiracy theory suggests the translators changed the text to please King Ptolemy II, the Egyptian Pharaoh who commissioned the translation of the Torah (the first five Bible books) for the Library of Alexandria.

There are no plausible reasons why the overwhelming majority of differences would, in any way, please Egyptian King Ptolemy. For example, Genesis 1:2 says that the earth was ‘formless and void’ in Hebrew, but implies it was hidden underwater in the Greek. Why would that be changed ‘to please King Ptolemy’?

It also doesn’t explain why:

- Jesus and the Apostles quoted from it.

- Many Hebrew Dead Sea Scrolls agree with it.

- Early Jewish writers accepted it.

- Archaeological evidence supports it.

Also, we only know for sure that the first five books of the Septuagint were translated under his reign. Many other Bible books were likely translated in the next century. Were they still trying to please a dead king?

This seems to be, in our view, an excuse often given by those who don’t like what the Septuagint says in some particular place, and they want a quick and simply story to explain the problem away.

Some others are upset that differences exist between the Septuagint and the Hebrew text, and feel like it shakes their faith. So they need an easy way to dismiss the Septuagint. It’s ironic, considering that the Septuagint contains more accurate prophecies and chronology.

A silly easy answer like this is known as a Fallacy of the single cause.

‘The Septuagint has Noah’s father Lamech die 2 years after the Flood!’

That is indeed how the numbers add up, and it’s impossible for Lamech to have died after the flood when only 8 people were in the Chest. So is this a valid reason to reject the Septuagint?

No.

With just a little knowledge and common sense, we can see why this objection has no merit.

1. The error was probably made by later copyists, not the Septuagint translators.

Our oldest copy of the Septuagint goes back to the 300s AD. That gives about 500-600 years for this tiny error to enter the text. And errors with numbers (and names) are some of the easiest errors to occur.

Does it make sense to reject a book because someone else added an error when copying it centuries later, even when that error is easily spotted and fixed?

How would you feel, if someone rejected everything you wrote, because someone else will add a typo to it 500 years from now?

2. Far worse errors appear in the Hebrew text’s numbers.

In multiple places, the Hebrew text has numerical errors:

- The timing of Nimrod’s cities,

- The number of David’s mighty men,

- The returnees numbers,

- Etc.

So by this logic, we should reject the entire Hebrew text too. In fact, we would probably have to reject every single codex of the Bible, leaving us with… Nothing.

3. The Septuagint is many different Bible books, translated by different people, over about 200 years.

Let’s say, for argument’s sake, that the error with Lamech was original (which is highly unlikely). Would it, therefore, be logical to reject all the Septuagint books, including those translated by other people a century later, because one previous book, done by a different person, has a minor numerical error?

How would you feel if you had translated a book, but then saw it rejected because someone else made an error, in another book, about 200 years ago? Does that make sense?

‘The Septuagint is a terrible translation!’

Sometimes, those who are aggressive in their preference for the Hebrew text (often because it says something they don’t like) will say things like this:

‘The Septuagint is a terrible translation, it’s full of errors!’

Actually, it’s not ‘terrible’, nor is it ‘full’ of errors.

Such detractors simply exaggerate its issues to dismiss what it says. Scholars believe some Septuagint passages reflect an earlier version of the Hebrew text (an earlier vorlage), as that suggests their Hebrew Bible has, indeed, been altered or reworded. This obviously upsets them, so they try to attack the Septuagint in any way they can.

It’s also an odd argument. If the Septuagint was really so bad, why did:

- Jesus quote from it?

- The Apostles rely on it?

- Many early Christians use it exclusively?

- Jewish scholars accept it for centuries?

- Greek-speaking Jewish communities use it for centuries?

- Eastern Orthodox churches preserve it?

- Dead Sea Scrolls confirm its readings?

In reality, yes, the Septuagint has some translation quirks and occasional errors (we’ve seen them while translating), but these are easy to spot and can be fixed.

Even an imperfect translation is valuable when it’s so much older than the Hebrew text, a text which we strongly suspect to have been deliberately altered or edited in key places. Rejecting the Septuagint for its easily spotted errors is like rejecting a person’s factually accurate account of an event, just because he misspelled some words. Misspellings can be spotted and fixed, correcting facts isn’t so easy!

Indeed, many of the supposed ‘errors’ in the Septuagint may actually be preserved original readings. Other ‘errors’ are actually helpful in explaining and clarifying how the text was understood by readers — people who lived thousands of years closer to the original writing than we are today.

Most other ‘errors’ are:

- Places where the translator expanded upon the original text to make it easier to understand.

- Places where the translator gave a more free translation, showing how they and their community understood it.

- Places where the translation from Hebrew is too literal, and sounds awkward in Greek.

These are not ‘errors’, at least, not strictly so; these things happen in all translations, and are sometimes preferred and desirable. True errors, such as mixing up a word, do happen here and there, but these are easy to spot and fix (we’ve spotted many ourselves).

So, do we want a text that contains the original prophecies of Jesus and the original chronology, even if it has some silly easy-to-fix translation errors? Or do we want a text that may have been altered to discredit Jesus, that contradicts the New Testament writers, and has a chronology that contradicts other Bible sources, history, and archaeology?

Indeed, we are not arguing that people should only use the Septuagint. The Hebrew remains priceless. There is no need to force ourselves to choose one over the other, for that would be a false dilemma.

Read The Letter of Aristeas

There is an ancient text that claims to be an historical account of the Septuagint’s creation. It’s called The Letter of Aristeas, and it’s a fascinating document.

It includes a description of how the Greek translation of the Torah was commissioned and produced, a travelogue of the author’s visit to ancient Jerusalem, and a record of a six-day-long banquet between the Jewish scholars and King Ptolemy, in which the King questions them about wisdom.