Circumlocutions for God’s Name

'O LORD (Hebrew: YHWH / יהוה), our Lord, how wonderful is Your Name on the earth!' –Psalm 8:9

God’s personal Name, YHWH (often pronounced Jehovah or Yahweh), is not found in most modern Bible translations. This isn’t because the Name was forgotten or lost to history. No, it’s due to a deeply rooted practice among ancient Jews and early Christians: using ‘circumlocutions.’ What are they?

Circumlocutions are indirect ways of referring to something without speaking or writing it directly.

Driven by deep reverence and a desire to avoid profaning God’s Name, Jews began using specific circumlocutions for it. These served as a deliberate signal, letting readers and listeners know when the Name YHWH was being referred to without having to actually say it.

It’s a bit like a euphemism, but instead of avoiding saying something unpleasant or offensive, it avoids saying something very holy.

The Name was widely used

When the Old Testament was penned, God’s personal Name, YHWH, wasn’t tucked away; it was front and center, appearing thousands of times throughout the sacred texts.

Yet it wasn’t just in the scriptures; ordinary people knew and used it, and it popped up everywhere from the Psalms (so we it was sung!) to everyday conversations. Even outsiders, like the Egyptian Pharaoh, used ‘Yahweh,’ as depicted in Exodus.

However, things began to change. It was replaced with ‘Lord’, continuing a very ancient tradition first used to avoid saying the names of false gods.

‘Baal’: A circumlocution for false gods

Saying ‘Lord’ instead of a god’s actual name, goes all the way back to the time of Moses. It was a way of avoiding saying the names of false gods. You see, ‘Baal’ was not actually the name of a god, it was a title meaning ‘Lord’, and it was used to refer to whatever false god was appropriate to the context.

That’s why you sometimes see the old testament refer to the ‘Baals’, meaning the local false gods. They obviously weren’t a bunch of different gods that all had the first name ‘Baal’! They were the local lords, or gods.

Now, the Israelites were not allowed to say the names of other gods:

‘…don’t mention the names of other gods or speak of them in any way.’ —Exodus 23:13

Therefore, a handy way of avoiding saying the names of false gods was to say ‘Lord’ instead, which was ‘Baal’ in the local language. This way, they didn’t need to break the law and say ‘Molech’ or ‘Ashtoreth’, and so on.

In other words, using ‘Lord’ to replace a god’s name is an extremely old custom, going back at least 3,500 years. The Jews just adopted the same custom for their own god, Jehovah/Yahweh.

Avoidance of YHWH begins

After the Jewish exile in Babylon, a custom developed among the Israelites to avoid saying God’s Name aloud. Whether it was out of immense reverence or perhaps a deep sense of shame over their exile (or a bit of both), the Name became, well, a no-go for casual conversation.

Certain rules were established, and they became pretty strict. For example:

-

By the 1st century AD, according to Philo of Alexandria, God’s Name may only be heard by ‘holy men’.

-

Later Rabbinic sources claim that the Name was only supposed to be said aloud once a year by the High Priest on the Day of Atonement in the Temple, while others say it could be said once a day in the daily sacrifices.

-

There were strict laws about discarding parchment that had the Name written on it, making it clear this wasn’t just any old word, but had to be treated with the utmost respect.

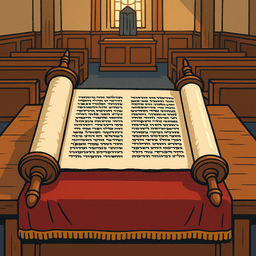

But what did people do when they read the Old Testament? It was very simple. Whenever the reader saw ‘YHWH’ they would not say it aloud. Instead, they would say ‘Adonai’ (Lord) or ‘Elohim’ (God). These became the circumlocutions for YHWH in Hebrew.

The circumlocutions in Aramaic

When Jewish exiles in Babylon started speaking Aramaic, they needed a way to refer to God’s Name without uttering it.

They used a few methods.

Over the centuries, the Aramaic Targums (retellings of Bible accounts) appeared:

- They’d use ‘YY’, an abbreviation of YHWH.

- Sometimes they’d replace it with entire phrases, such as ‘the word of the Lord’, or ‘Divine Presence’.

- Othertimes, they’d just say ‘Lord’.

The word for ‘Lord’ they used would usually be Marah. But there was an even more reverential version, MarYah.

- Marah = ܡܪܐ / מרא

- MarYah = ܡܪܝܐ / מריא

The Marah (and sometimes just Mar) version would both substitute YHWH and refer to ordinary human ‘lords,’ but they reserved the full MarYah for the most important, highest lords, like, you guessed it, God. So while Marah could mean God or any Lord, MarYah would almost exclusively replace YHWH in Aramaic texts, particularly in the Peshitta, the Aramaic translation of the Bible.

It was also a neat coincidence that MarYah ends with Yah, reminding everyone of the shortened form of God’s Name. So, it might have sounded like ‘Lord Yah’, even if it didn’t literally mean that. It wasn’t a Jewish invention; it’s an Aramaic word used in Syrian and Babylonian royal courts.

We can see Marah and MarYah used thousands and thousands of times to replace YHWH in the Aramaic Targums and the Aramaic Peshitta translation of the Bible.

These same circumlocutions of God’s Name are used in the Aramaic version of the New Testament 139 times, both when quoting the Old Testament and in other contexts too.

- Learn more: God’s Name in Christian Texts

- Learn more: Maryah: The Aramaic Way to Say ‘Jehovah’

The circumlocutions in Greek

As Jews spread out and adopted Greek, the same circumlocution game continued with κυριος (kyrios), the Greek word for ‘Lord’. Here’s where it gets a little quirky: they would use κυριος (kyrios) without the definite article (‘the’) beforehand.

Normally, that’d be a flat-out grammar error — like saying ‘Lord went to market’ instead of ‘The Lord went to market.’ But in this case, it was entirely on purpose!

This missing ‘the’ was a special, deliberate signal to readers. It told Greek-speaking Jews, loud and clear:

‘Hey, right here? This is where YHWH originally stood in the Hebrew text!’

So it wasn’t an ‘error’ at all, but a well-established custom, a secret handshake, if you will, letting them know when ‘Lord’ was stepping in for God’s Name.

You can see this used thousands of times in the Greek Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament (made in the 1st to 3rd century BC).

The exact same thing was used in other (non-Biblical) Koine Greek texts, such as 1 Maccabees, and even in apocryphal works like 1 Enoch. Later, it would be used 102 times in the New Testament, both when quoting the Old Testament and when talking about God.

So yes, God’s Name ‘appears’ in the New Testament, but only as traditional circumlocutions.

- Learn more: God’s Name in Christian Texts

The circumlocutions in the Hebrew Masoretic Text

Fast forward a few centuries, and Jewish scribes (known as the Masoretes) were preserving and standardizing the Hebrew Bible texts. Even though written Hebrew didn’t originally include vowels, the Masoretes added ‘vowel points’ to guide pronunciation.

Now, when they came across YHWH, they didn’t add its actual vowels. Instead, they supported the existing tradition of saying ‘Lord’ or ‘God’ by cleverly inserting the vowel points from words like ‘Adonai’ (‘Lord’) or ‘Elohim’ (‘God’).

It was a subtle, yet effective, heads-up to readers:

‘Remember: Don’t say YHWH here! Say ‘Lord’ or ‘God’ instead!’

- Check out our article God’s Name.

The circumlocutions in English

Originally, most Christian Bibles were based on the Greek Septuagint, which used κύριος as a circumlocution for YHWH. So Christians merely continued the tradition of using ‘Lord’ instead of God’s Name. They did not actively remove or censor it, they simply continued what had already been the custom for centuries.

However, in later times, when European translations were made directly from Hebrew, the translators had to make a choice: They could either use ‘Lord’ or ‘God’ as a circumlocution for YHWH, or they could actually use God’s Name…

They mostly chose to continue using ‘Lord’.

However, in a later centuries, translators and publishers would show the reader where YHWH had been replaced with 'Lord' by using SMALL CAPITAL LETTERS or other signals. These include:

-

William Tyndale (1520s) used ‘LORde’ (putting the first three words in uppercase) to show where it was originally YHWH. This copied Martin Luther’s ‘HERr’ in German.

-

The Geneva Bible (1560) would use the word LORD (in smaller capital letters) to show where it was originally YHWH. This became a very influential Protestant Bible.

-

The Bishops’ Bible (1568) would use the word LORD (in capital letters or some other emphasis) to show where it was originally YHWH. This was the official Church of England Bible before the KJV.

-

The King James Version (1611) would use LORD (in smaller capital letters) to show where it was originally YHWH. This became the new official Anglican Bible.

The tradition continues to this day, seen in the Revised Version (1885), Revised Standard Version (1952), and the English Standard Version (2001). However, most modern translations do not tell their readers anything about where the name was replaced with a circumlocution.

God’s Name in our translation

Our translation uses God’s Name wherever it appears in the original source texts — either literally in Hebrew, or as circumlocutions in Greek and Aramaic. By default, it appears as Jehovah, but you can change it to Yahweh in your settings. You can also choose to see the original circumlocution, if you wish.

We strongly believe that showing the Name is both the right thing to do and the best thing to do. Why?

Educating the reader

If we don’t, then modern readers may continue to have no idea that God’s Name was once used in the text.

Modern readers, generally, have no idea when a circumlocution is being used. Most people have never even heard of a circumlocution! Even many users of the King James or Revised Standard Version don’t know why ‘Lord’ sometimes appears as capital letters.

But it gets worse. Replacing God’s Name with a circumlocution confuses and muddles certain verses.

Clearer verses

For example, in the Greek Septuagint version of Isaiah, God is often referred to as:

‘Kyrios ho Kyrios’

Or:

‘Lord the Lord’.

Ancient readers knew the circumlocution game, and understood such sentences as meaning this:

‘Yahweh the Lord’.

Many modern readers, though, don’t know anything about this. Worse still, some translations of the Septuagint then ‘fix’ the awkward wording by mistranslating the entire phrase as, ‘Lord God,’ or ‘Sovereign Lord.’ Yes, they hide the fact the Name was ever there, and even distort the text to completely erase the problem.

Similar problems even occur in Bibles translated from Hebrew.

In most Bibles, Psalm 110:1 reads like this:

‘The Lord said to my Lord…’

How confusing! Who is talking to whom? Yet the original wording was not confusing. It said:

‘Yahweh said to my lord…’

When modern translations don’t tell their audience anything about circumlocutions, readers will sometimes be left scratching their heads, and occasionally they may completely misunderstand the text.

For these reasons, you’ll find God’s Name throughout our translation, restored to its rightful place, just as the original authors intended. We also show Jehovah/Yahweh in the New Testament, translating the same circumlocutions present there to say exactly what they mean.

- Learn more: God’s Name in Christian Texts

God’s Name

-

-

-

-

-

-

Also see our Articles index and our About section.